- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

Before Digital: The Magic of Early Photography

by Angela Fuller, Assistant Curator, and Tamera Lenz Muente, Curator

As the title of the Taft Museum of Art’s summer exhibition suggests, photographs are perceived as capturing a “moment in time.” In reality, a photograph is the culmination of many steps, beginning with a photographer’s vision and, for the earliest images, a camera exposure time ranging from several seconds to several minutes. Technology, chemistry, darkroom manipulation, and printing techniques can also play a role in the appearance of a photographic image. Even today, when snapping a photo with a smartphone is instantaneous, a well-made photograph involves much skill and artistry. Moment in Time: A Legacy of Photographs / Works from the Bank of America Collection offers us the opportunity to examine, up close, many fascinating photographic processes from the pre-digital age.

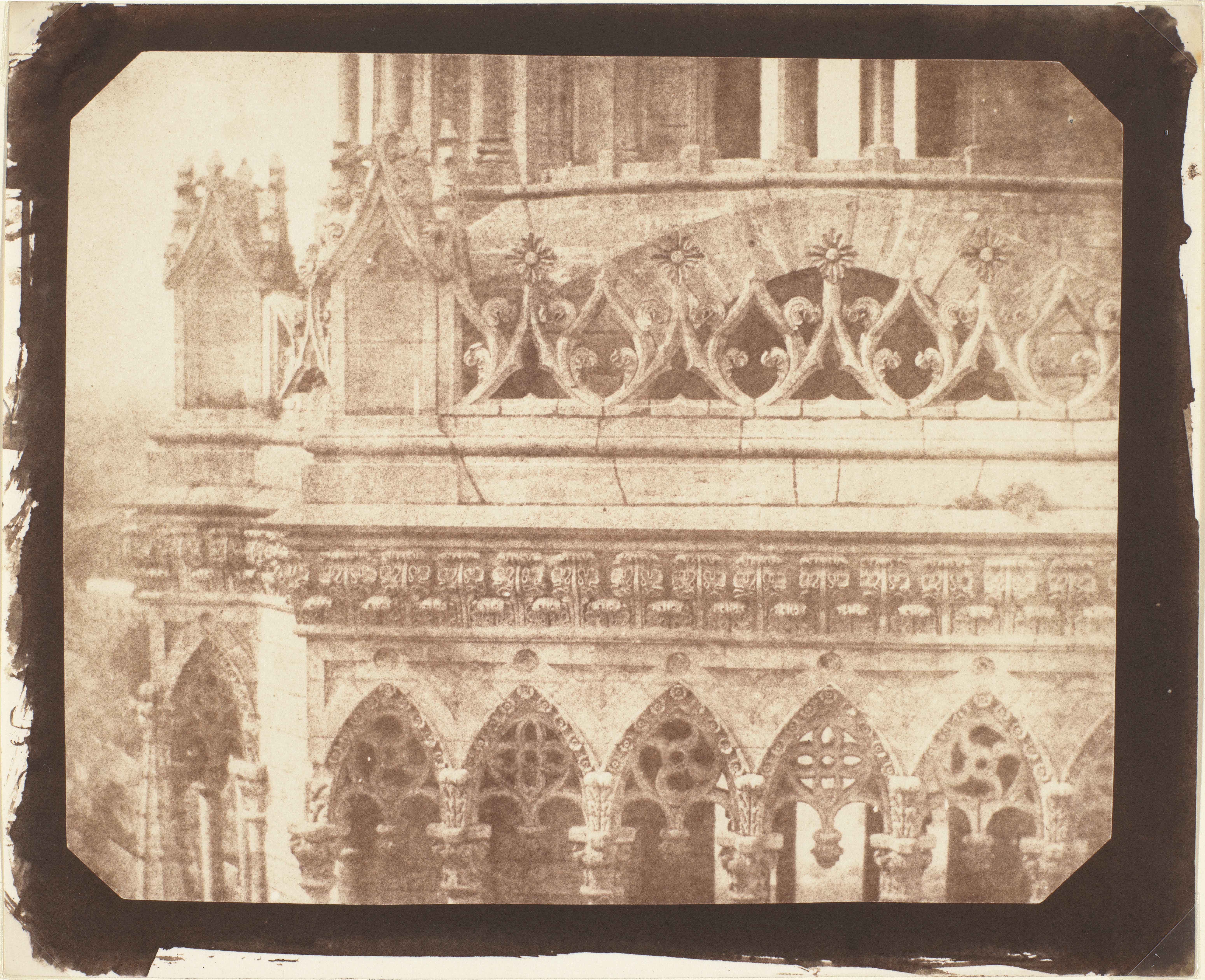

Calotype/Salted Paper Print

In 1841, British scientist William Henry Fox Talbot patented the first photographic process employing a negative, an image that reverses light and dark and can be used to make multiple positive images, called prints. To make a calotype, also known as a Talbotype, a photographer first saturated paper with silver iodide, silver nitrate, and acids to make it light-sensitive. After exposure to light in a camera, the photographer used additional chemicals to develop and fix the resulting negative image within the paper. Talbot produced prints from his calotype negatives using a method called salted paper printing. He sensitized a new sheet of paper to light with salt and silver nitrate, placed it under the calotype negative, and exposed them to sunlight. The calotype process produced a softer and less detailed image than the daguerreotype, which became popular in the United States.

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 1800–1877), Orléans Cathedral, 1843, salted-paper print from calotype negative. Bank of America Collection

-

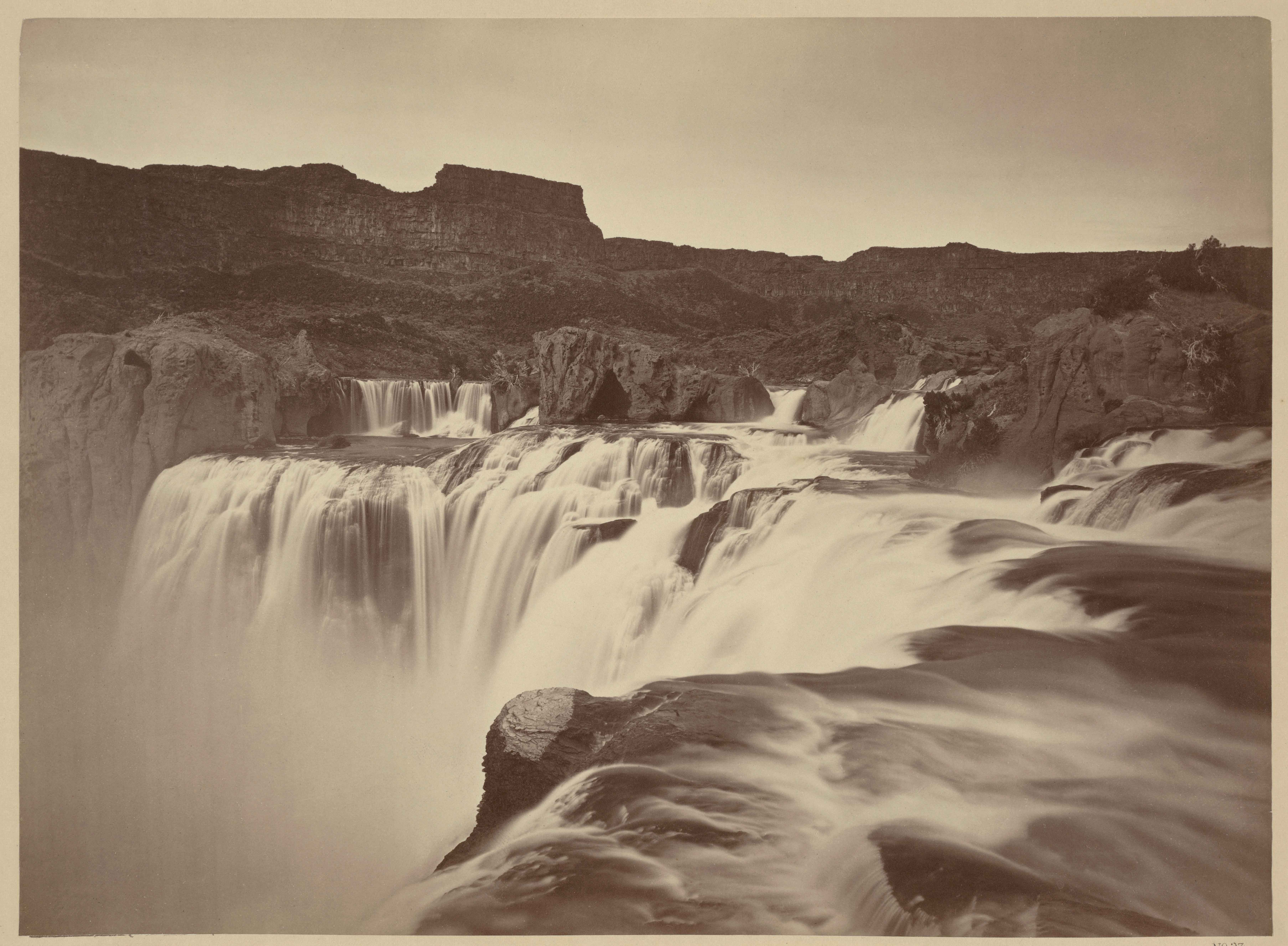

Albumen Silver Print

The most popular photographic process during the second half of the 1800s, albumen prints were made by coating paper with a solution of egg white and salt. The paper was then treated with silver nitrate and chloride to sensitize it to light. The photographer placed this coated paper behind a glass-plate negative in a printing frame and exposed it to sunlight. The light passed through the negative, causing the image to emerge on the paper without the application of further chemicals. The photographer placed the print in a solution that fixed it to the paper, then washed and dried it. Since the image was suspended in the egg white emulsion on the surface rather than embedded into the paper fibers, albumen prints produced shiny, crisp, high-contrast images.

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American, born Ireland, about 1840–1882), Shoshone Falls, Snake River, Idaho: View across the top of the Falls (Wheeler Survey) #23, 1874, albumen silver print. Bank of America Collection

-

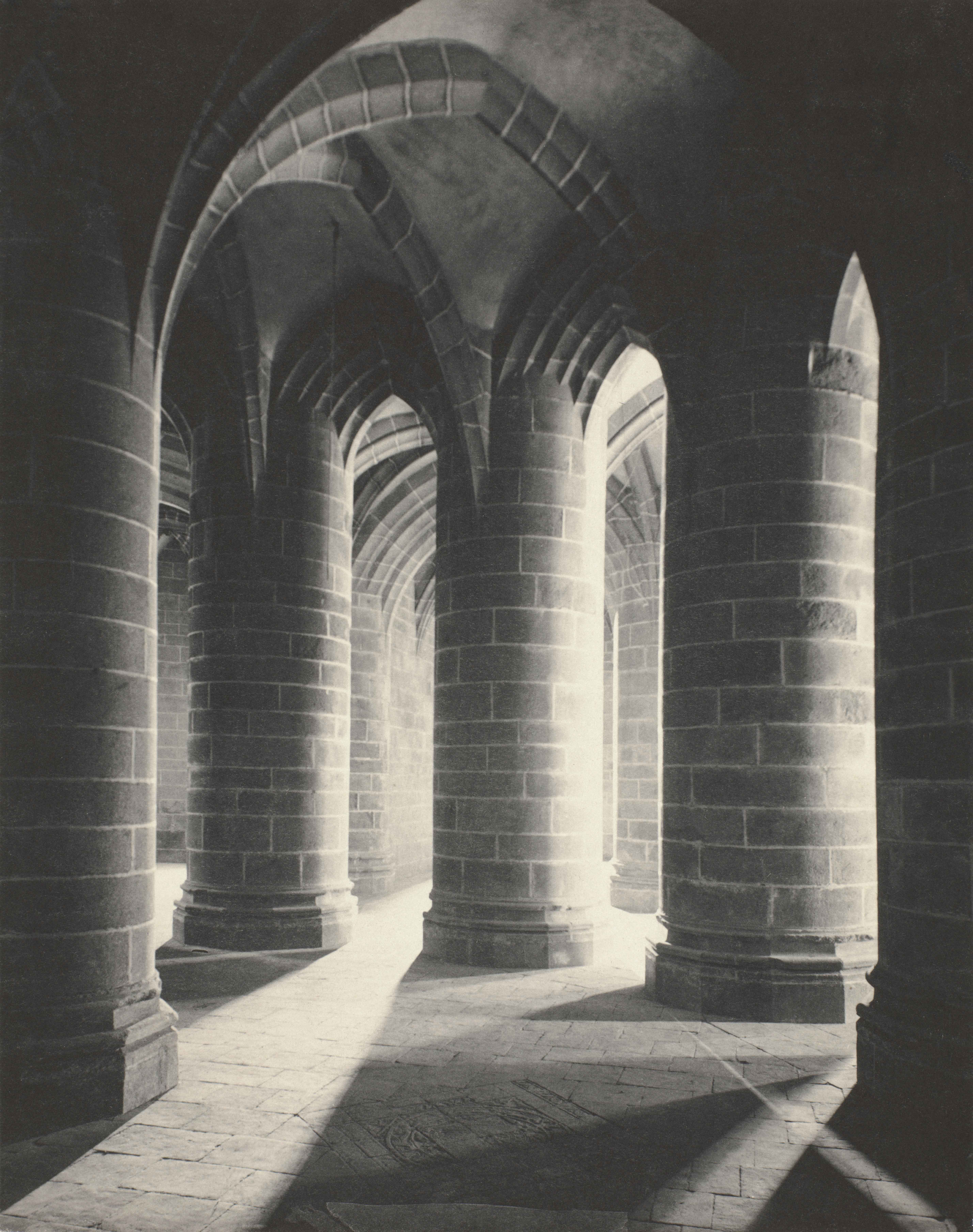

Platinum Print

More costly than silver, platinum also becomes light-sensitive when combined with iron salts. Characterized by their rich darks, subtle highlights, and nuanced midtones, platinum prints require no emulsion coating. Instead, the image is embedded inside the paper, creating a soft, matte appearance that varies depending upon the paper used. Platinum-treated photographic paper was commercially available beginning in the 1870s, but the demand for platinum during World War I limited its availability and increased its price. Platinum prints are highly stable—they resist tarnish, corrosion, and fading.

Frederick H. Evans (British, 1853–1943), Mont St. Michel Crypt, 1906–07, platinum print. Bank of America Collection

-

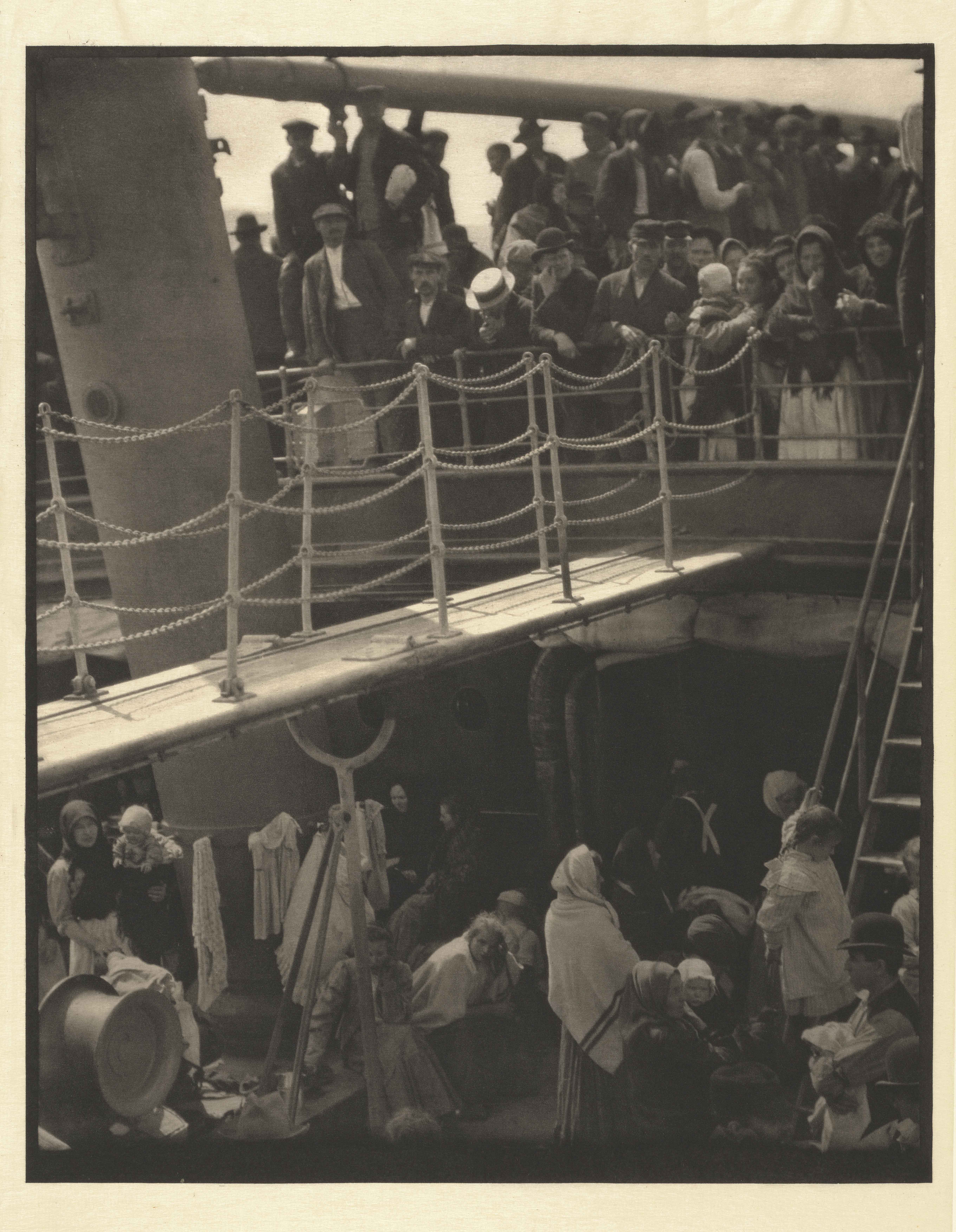

Photogravure

Alfred Stieglitz, a passionate early advocate of photography as a creative art form, included many photogravures in his pioneering journal Camera Work. Characterized by their tonal variation and soft resolution, photogravures are printed one at a time from an inked copper plate. First, a positive transparency is laid on light-sensitized, gelatin-coated tissue paper and exposed to light, which hardens the gelatin in proportion to the light exposure. The tissue is laid on a copper plate, and both are soaked in water to adhere the gelatin to the metal surface. The tissue and unhardened gelatin is washed away in water. The plate is then placed in acid that etches depressions into areas unprotected by gelatin. Ink rolled onto the plate collects in the depressions. Finally, paper is laid on top of the plate, which is then squeezed through a press, transferring the image to the paper.

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946), The Steerage, 1907, photogravure. Bank of America Collection

-

Gelatin Silver Print

Gelatin silver offered several advantages over albumen: the process allowed smaller negatives to be enlarged, required shorter printing times, and the images resisted discoloration over time. Paper coated with silver salts suspended in gelatin first became commercially available in the 1880s. To make a print, a photographer placed a negative into an enlarger and projected light through it and onto the coated paper. The image appeared after the paper was placed in a developing solution. Finally, the photographer placed the print in a second solution to prevent it from further reacting to light, then washed it in water. With their glossy surface and crisp details, gelatin silver prints became the most widely produced photographs until the advent of color photography in the 1960s.

Yousuf Karsh (Canadian, born Armenia, 1908–2002), Marc Chagall, September 20, 1965, 1965, gelatin silver print. Bank of America Collection. © Yousuf Karsh

-

Dye-Transfer Print

By the 1930s, various color processing methods had emerged. They were expensive, complex, and difficult to control, so most fine art photographers continued to embrace black-and-white until the 1960s and 1970s. Eliot Porter, however, became a leading proponent of the dye-transfer process in fine art photography beginning in 1946. A painstaking, multistep process, dye-transfer achieves brilliant color through the use of three separate negatives. The photographer uses these negatives to make three gelatin layers of dye: cyan, magenta, and yellow. Each layer is hand-rolled onto a final sheet of paper one at a time to transfer each color separately, requiring perfect alignment.

Eliot Porter (American, 1901–1990), Maple Leaves and Pine Needles, Tamworth, New Hampshire, about 1956, dye-transfer print. Bank of America Collection. © 1990 Amon Carter Museum of American Art