- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

Charles and Anna Taft | Community-Minded Collectors

The Inside Story

At the turn of the 20th century, few art collectors in Cincinnati shared the passion and determination of Charles Phelps Taft and Anna Sinton Taft. The couple’s interest in art likely was sparked in their youth, when each traveled (and in Charles’s case, studied) in Europe years before they married. After finishing law school in 1866, Charles completed his doctorate in Germany, where he visited museums in Berlin and Dresden. After graduating, he traveled around Europe and the United Kingdom, and wrote about his fascination with art, architecture, and culture in his letters home. Anna and her father, David Sinton, traveled to Europe in 1870, when she was about 18 years old. Not much is known about the Sintons’ trip, but viewing art was a requisite of any European tour, and they did visit the Cincinnati painter Thomas Buchanan Read in Rome and had their portraits modeled by another expatriate Cincinnatian, Hiram Powers, in his Florence studio.

After they married in 1873, the Tafts became involved with many fledgling arts institutions. Three years before the Cincinnati Art Museum’s founding in 1881, Charles delivered a lecture to the Women’s Art Museum Association, whose members—including Anna—worked to convince leaders that the city needed an art museum. In his talk, Taft outlined his belief in the ability of art to “educate the mind and eyes . . . of the great mass of the people” and to “relieve the . . . distress of our idle population by opening new industries or enlarging the scope of those already existing.” Charles was building upon ideas from London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum), an institution that would later influence his and Anna’s own collecting. This museum emphasized the decorative arts, stressing that, as Charles put it, “every artisan should derive inspiration from the best works of his handicraft.”

When David Sinton died in 1900, he left Anna, his sole heir, an estate worth about $20 million (the equivalent of over $600 million today). Charles and Anna set in motion their plans to use their newly inherited wealth to benefit their hometown and to build an art collection. Charles wrote to his brother, William Howard Taft, in 1903, “Annie and I have about made up our minds that it would be just as well to invest money in pictures as to pile it up in bonds and real estate. At all events, we get a good deal of pleasure out of pictures.” At first, the Tafts purchased mostly paintings by living European artists, which they later sold or traded for more significant treasures. Between 1901 and 1903, they traveled abroad to look at art in museums and private collections, visited New York dealers and museums, and read about art in catalogs and other publications. As they educated themselves, their interest in the decorative arts grew; eventually, decorative arts would make up about three-fourths of their collection.

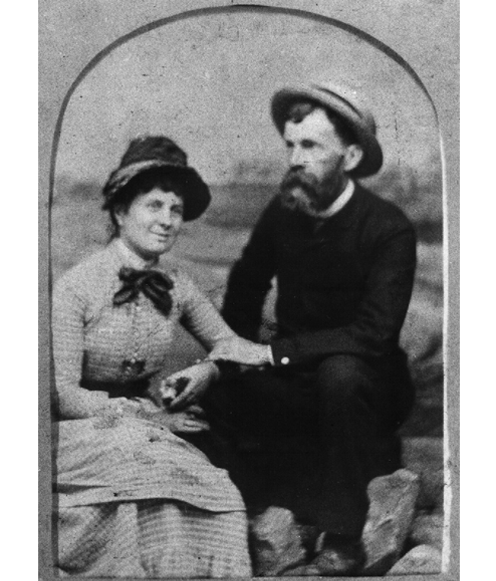

Charles Phelps Taft and Anna Sinton Taft, about 1880; after an original photograph in the collection of the William Howard Taft National Historic Site (United States National Park Service)

The Tafts’ interest in collecting went beyond personal pleasure. As Charles had discussed in his lecture almost 30 years earlier, the couple sought to provide inspirational and educational models for artists and craftspeople to fuel the quality of items made in Cincinnati and to increase opportunities for skilled artisans in the local economy. By the turn of the 20th century, Cincinnati had become a center for art pottery, and the more than 200 pieces of Chinese ceramics the Tafts purchased were likely intended as a resource for the industry. Their ceramics may have influenced shape designs and glazes created by Rookwood Pottery, which released a Chinese-inspired pottery line in 1915. Cincinnati was also home to several watchmaking firms, and the Tafts may have acquired their collection of watches to inspire these artisans, who mostly crafted decorative watch cases. The paintings they collected provided excellent examples of old master European portraits, landscapes, and scenes of daily life—exactly the subjects in demand from Cincinnati’s own working artists.

Beginning in February 1903, the Tafts made their collection available for viewing by inviting artists, artisans, and others to their home on select Sunday afternoons. They also shared their collection with the wider public by lending it to the Cincinnati Art Museum for an exhibition in 1911. In 1927, the Tafts bequeathed their collection and home to the people of Cincinnati “in such a manner that they may be readily available to all.” This generous gift, along with an endowment that would support their newly created museum, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Conservatory of Music, and the Cincinnati Art Museum, left a legacy that continues to give back to the Cincinnati community generation after generation.

For the content of this article, the author gratefully acknowledges Lynne D. Ambrosini for her research and her essay “Charles and Anna Taft: Forming a Gilded Age Art Collection,” from Taft Museum of Art: Highlights from the Collection, London: D Giles Limited, 2020.