- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

Art Conservation

By Betsy Allaire, Allaire Fine Art Conservation, LLC

When an art object is going to be photographed for publication, it needs to look its best. The Taft has been photographing some of its artworks for an upcoming book that will feature 80 highlights of the Museum’s collection. It will be published in the fall of 2020. One of the Taft’s treasures, the splendid but badly tarnished 17th-century Two-Handled Covered Cup, was brought to the Museum’s conservation lab to be cleaned and stabilized prior to photography (fig. 1). (The Taft has a lab on site for the use of different contract conservators, each of whom specializes in certain kinds of art objects.)

This decorative mid 17th-century German cup, which is perennially on view in the Keystone Gallery, was not intended for use but for admiration and as a display of the power and wealth of the owner. It is a fine example of Baroque-era decorative arts.

Fig. 1: Two-Handled Covered Cup, before treatment

The two parts, cup and cover, are made from richly colored moss agate. The colorful finial, ornate handles, and exquisite bases are embellished with silver elements, coated with gold. The foot of the cup and lower band of the cover are adorned with fanciful raised enamel cagework floating above the silver foot. This cagework is highlighted with mounted semi-precious stones and lively multicolored enamel depictions of floral elements and graceful birds. The crowning ornament on the cover and the upper attachment points of the two figural handles are likewise adorned with semi-precious stones and brightly enameled fruit and flowers, but here the enameled elements are three-dimensional.

As a conservator approaching any object with the intention of improving its appearance, I begin by asking questions: What materials are present? What is going on with the materials? What can they tell me? So, in this case, I began by considering what I know about the materials, how they degrade, and how to identify the material’s behavior in this situation. When I examined the cup, I was able to identify gilt silver—a process in which gold, sometimes only microns thick, is applied to the surface of the silver decoration. While pure gold does not tarnish, gilt silver can, and, yes, tarnish was present here, caused by atmospheric pollutants interacting with the metal surface.

Of course, tarnish is commonplace, and easily recognizable in museum and household collections. But removing tarnish from gilt silver isn’t as easy as polishing your own silver with a paste cleaner, since abrasive polishes can remove the thin gilded surface. Instead, conservators use solvent cleaners when cleaning gilt silver—but with great caution in order to avoid future corrosion caused by chemicals left behind.

The enameled surfaces of the cup also told a story. I saw localized degradation of the enamel, a situation that is less commonplace than tarnished silver. Enamels are composed of layers of glass powder vitrified (or fused) onto the surface of the metal, and enamel can degrade over time.

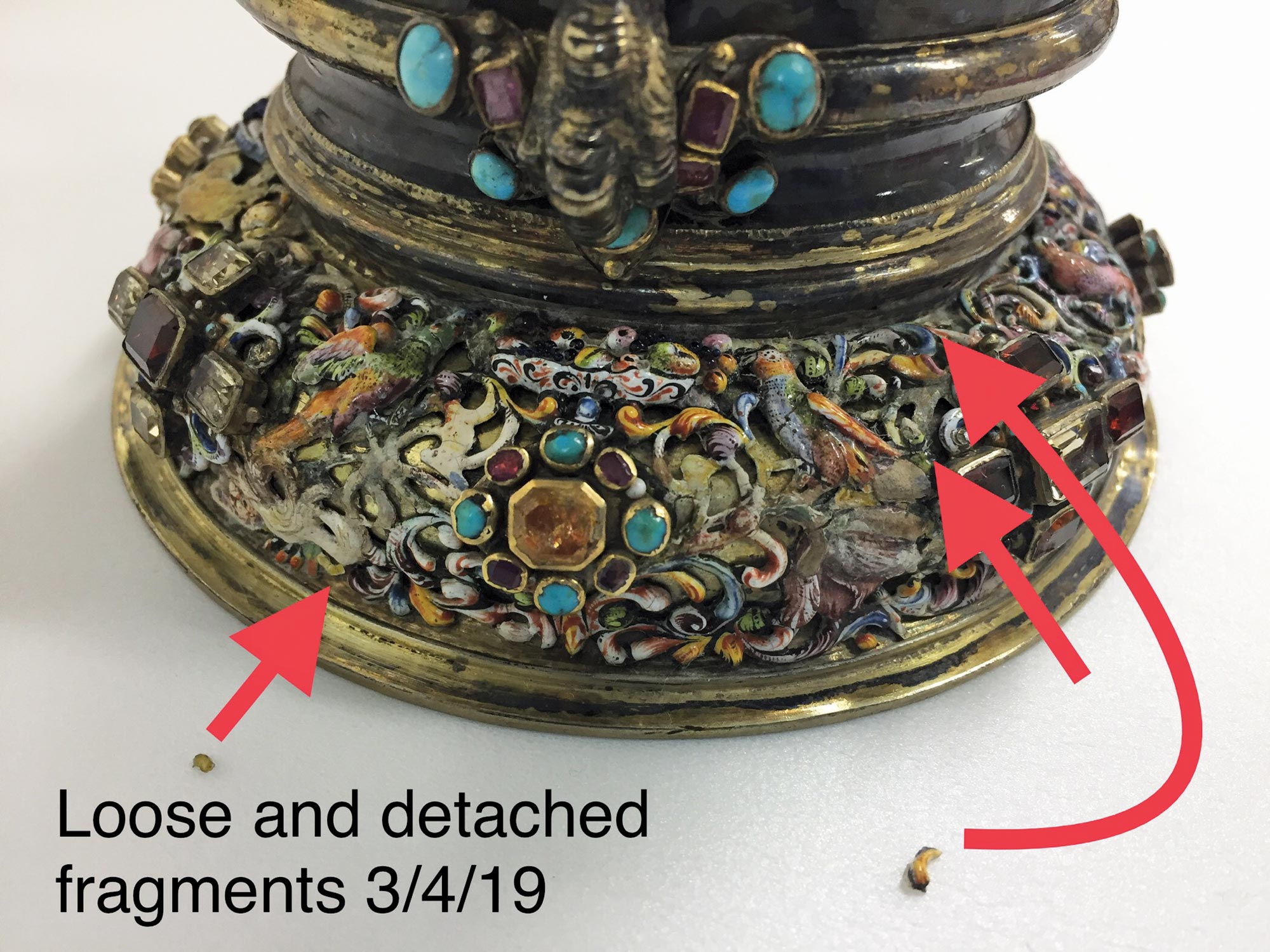

While it is difficult to envision instability in a material as hard and reliable as glass, if the chemical composition of the enamel is not balanced correctly upon manufacture, chemicals can leach out of the matrix of the glass, leaving voids in the structure. Micro-cracks form, compromising the enamel’s visible legibility— meaning basically that its appearance is altered—and structural stability. In conservation, deterioration of this variety is referred to as “inherent vice,” because the cause of the deterioration is intrinsic to the material of which the object is made. In areas of the covered cup, you can see some loss to the readability of the surface decoration (these areas appear to be chalky white—see fig. 2) and, in other areas, minor losses to the structure of the enamel. During treatment, I located and reattached several loose fragments found caught in the cagework (see fig. 2). Although there is no way to reverse the degradation of the enamel, it can be slowed if the object is kept under stable environmental conditions.

Fig. 2: Two-Handled Covered Cup, base during treatment

Figure 3 (left): after treatment, Possibly Johann Zeidler, Two-Handled Covered Cup, Nördlingen, Germany, mid-17th century, moss agate, silver-gilt, and enamel on copper with rubies, garnets, emeralds, sapphires, citrine, and turquoise. Taft Museum of Art, 1931.267

The materials that compose or decorate an object, and the way those materials behave over time, can tell an interesting story—a story prolonged by good recordkeeping, stable environmental conditions, and careful handling. Past museum records of examination of the Taft’s Two-Handled Covered Cup show that only minor changes have occurred in this artifact over the past several decades. Most areas of its enamel are stable, and the bright colors of the painted decoration look vibrant next to the colored stones and agate body. Through conservation treatment, I was able to reduce corrosion and stabilize at-risk areas, improving the appearance of the metal decoration so that we can continue to enjoy the craftsmanship and beauty of this refined object for centuries to come (fig. 3).